PS - now (mid-December, 2020) that a ceasefire and change of territory has been agreed and is being implemented, HRW has released reports into human rights abuses by both sides.

“Stop the Press” - Russia has mediated

a ceasefire (that’s great, but it must start, and then continue - and

it isn’t a peace)

The events over the last week and a bit in Nagorno-Karabakh, a rugged and predominantly Armenian region that has been more or less self-governing since around 1988 (talks over the region’s fate commenced when the fighting stopped in 1994) but is located inside the predominantly Muslim Republic of Azerbaijan, located as little as a few kilometres from the predominantly Christian Republic of Armenia, have been terrible - hundreds are dead, many more have been wounded, destruction of property has occurred - lives have been stopped, altered, and crippled by fear, loss, and change imposed by the will of others.

I and others can relate to the sensation of being surrounded by a hostile and sometimes violent group: it is something that women, members of minority groups (ethnicity and religion), LGBTIQ+ people, and members of various classes in society all have experienced . . . but we, here in Australia, don’t have artillery firing at us, jets dropping cluster bombs, and snipers picking off our loved ones.

We actually have past connections with that region:

- the invasion of Gallipoli in 1915 was the trigger for an increase of attacks by the Ottoman Empire against Armenians; but

- towards the end of World War One, Australian troops were involved in saving some Armenians, with a platoon or company fighting off a larger detachment of Ottomans for more than a day so the Armenians could escape; and

- “Doc” Evatt played a key role in developing the United Nations (UN), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which were major steps towards the development of the Genocide Convention, a crime that was named by Raphael Lemkin after he heard of the Armenian Genocide - a convention which Australia has ratified; but

- Australia continues to officially refuse to acknowledge the Armenian Genocide . . .

(Samantha Power covers these matters well in her book “A Problem From Hell”.)

This is the sort of situation I often hear people say “oh, that’s very complicated”, “oh, that’s an old problem”, (implying it is intractable), all of which is basically an excuse not to care or try.

I actually consider the situation in this region not very complicated, and entirely predictable, predicated on the arrogant, uncaring, self-interest of the various Empires that have shoved their tentacles - the USSR most recently, but before them (separated by a period of independence) the Ottoman Empire, and before that (Tsarist) Russia, Persia, Arabs, and even the Roman Empire.

These clashing and competing Empires are basically putting their desire for macho braggadocio (I phrased that much more crudely for the first few version of this post, but toxic masculinity is, in my opinion, a major part of all empire building and sovereignty-based problems - whereas healthy expressions of masculinity can be part of the solution) ahead of the wellbeing of others - not to mention others’ right to self-determination.

The right to self-determination, by the way, existed before it was codified, in my opinion: all the codification did was, as with Newton’s Law of Gravitational Attraction, provide a description of something that already existed - morally, if not normatively.

What those Empires did was similar, in many ways, to what European colonial powers did with arbitrary borders in Africa (well discussed in books like David van Reybrouck’s “Congo”, and books like the “Very Short Introductions” to “African History”, written by John Parker and Richard Rathbone and “African Politics”, written by Ian Taylor).

Stalin, in particular, had a well developed sense of divide-and-rule and buying loyalty which led to this region being given to Azerbaijan.

That decision led to the current situation, as when the USSR collapsed decisions were made to put the sovereignty of created nations ahead of the right to self-determination of peoples - something that led to wars and other problems in Africa.

I support both those principles - sovereignty and the right to self-determination, but when the two clash, the latter must take precedence (just as, at present [during the COVID-19 pandemic], the right to health and life is taking precedence over other rights). When that order of precedence does not occur, when sovereignty is taken to have precedence over other rights such as the right to self-determination, we have empire building, abuse of asylum seekers, and discrimination, to name just a few of the resultant problems.

It is, in my opinion, about people feeling they are lessened by allowing others to have reasonable, deserved and rightful freedom.

Going back to list of groups I gave earlier (women, members of minority groups [ethnicity and religion], LGBTIQ+ people, and members of various classes in society), this is something that they have often had to endure as well, so it should be understandable - or at least relatable.

The history of discrimination by Azerbaijanis against Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh is not helping anyone - not even those sadistic bigots who get off on their petty and arbitrary imposition of power through abuse, which is a problem that the listed minorities also experience - wherever they are.

Azerbaijan never really “had” Nagorno-Karabakh, therefore it will not be lesser if it lets that region go, much as men in patriarchies are not diminished by allowing women equity. They may think so, because they are uncomfortable at the change, but they are removing psychological scars and burdens from themselves. As an example of that, the drive for women’s rights has now made it easier for fathers to be part of their children’s lives. On an international scale, the United Kingdom “lost” the colonies that became the USA - which established a healthy (“special”) relationship with, and then saved, the UK (and the rest of the world) in the World Wars.

The UK also “lost” India, which allowed India to start recovering from the damage British occupation had caused (India’s GDP had been 20% of the world’s total before the British invasion, but was only 5% after), weakened the arrogance that was so problematic in British Imperial thinking, and freed the UK of some of the moral burden it had as a result of its actions - actions involving military rule/occupation are always expensive, and the UK could no longer afford to try to impose rule.

Azerbaijan spends a significant part of its GDP on military matters: if it stopped trying to impose “rule” on Nagorno-Karabakh, it would remove that expense, and avoid the loss of human potential that such conflict always causes, including the loss of thinking resulting from the distracting focus on dominating and/or hating a region/people. How many Lotfi A. Zadeh’s has this conflict robbed Azerbaijan of?

The same impacts and losses have also been felt by Armenia.

Terrible as that is, there is also the question: could this conflict spread?

Together with most of the nation of Georgia (a pro-Western [since 2003] “parliamentary constitutional republic” which has two border disputes with Russia that last flared into war in 2008), Nagorno-Karabakh, Armenia, and Azerbaijan make up what is called the South Caucasus or Transcaucasia - a region from Russia’s Greater Caucasus mountains in the north to the borders of Turkey and Iran in the south, and from the Black Sea in the west to the Caspian Sea in the east - an area of just over 180,000 square kilometres and around 17 million people (10 million in Azerbaijan, 150,000 in Nagorno-Karabakh), a broad valley between and partly in two mountain ranges with oil, manganese, and good agriculture (this region may have been where the first wines were made, many thousands of years ago).

This region has a history of being forced into one conglomerate by various powers - most recently Soviet Russia, until 1991. Armenia and Azerbaijan are members of the post-USSR organisation the Commonwealth of Independent States; Georgia withdrew from the CIS after the 2008 war with Russia.

A short overview of nations in this region is:

- Armenia is rated

“partly free”, and, although it is not good, its human

rights situation

tends “to be better than those in most former Soviet republics and have

drawn closer to acceptable standards”, and there has been some progress.

The nation had, in 2017, a GDP of US$28 billion (4.9% [7th most in the world] spent on its armed forces of around 45,000), US$9,500 per capita across its approx. 3 million people, with 32% below the poverty line.

From a governance point of view, using World Bank data, the nation has generally improved since the USSR ended, excepting political stability in the last couple of years, but still has a way to go.

- Nagorno-Karabakh is rated as “partly free”, and, well, see here, for example, regarding human rights.

- Azerbaijan is rated as “not free”, and

significant concerns

exist about human rights in

that nation.

The nation had, in around 2017 a GDP of US$172 billion (4% [10th in the world] spent on its military of 67,000 active personnel), US$17,500 per capita across its approx. 10.2 million people, with 4.9% below the poverty line. 90% of Azerbaijan’s exports are oil and gas, with the key customers being (in 2017): Italy 23.2%, Turkey 13.6%, Israel 6.1%, Russia 5.4%, Germany 5%, Czech Republic 4.6%, and Georgia 4.3%.

From a governance point of view, Azerbaijan has improved only slowly since the USSR fell - the low respect for Rule of Law, given the current circumstances, is of particular concern.

- Georgia is rated “partly free”, and

there are concerns

about human

rights and ineffective

attempts at political reform (but the attempts were made).

The nation had, in 2017, a GDP of US$40 billion (2% [50th in the world] spent on its military of approximately 25,000 active personnel), US$10,700 per capita across its approx. 4 million people, with 9.2% below the poverty line (in 2010).

From a governance point of view, Georgia has made considerable improvement since the Rose Revolution, and is in a reasonable state now, except with regard to political stability.

Moving on to other regional players:

- Turkey is rated “not free”, and there

are serious

concerns about human

rights, particularly

following the attempted

coup in 2018. Turkey is actively intervening in Syria.

The nation had, in 2017, a GDP of $2,190 billion , US$27,000 per capita across its approx. 84.6 million people, with 21.9% below the poverty line in 2015.

From a governance point of view, this nation has been showing a decline over the last half decade or so.

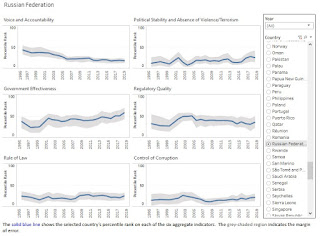

- Russia is rated “not free”, and there

are grave

concerns about its deteriorating

human

rights situation. Russia is also actively intervening in several conflicts

in West Asia and northern Africa.

The nation had, in 2017, a GDP of $4,020 billion (3.9% [14th in the world] spent on its military of 900,000 active and 200,000 National Guard personnel), US$27,900 per capita across its approx. 146 million people, with 13.3% below the poverty line in 2015.

From a governance point of view, this nation is of concern, despite government effectiveness having increased. Rule of law is disturbingly low for a nuclear armed nation.

So, my summation of all those numbers is:

this is a region of relatively poor (despite the resources of the region) and small (my home city has more people than Armenia and Georgia) nations, with significant military spending by Armenia and Azerbaijan. Georgia and possibly Armenia are moving towards Western style democracy and freedoms, but all three are affected by:

- historical events,

- the ongoing legacy of the USSR’s abuses,

- the present tensions of being minnows between the ambitious, unfree, abusive, interventionist and authoritarian Russian and increasingly authoritarian Turkish sharks, and

- the hassle of trying to co-exist with differing cultures in the same valley which happens to be in a reasonably significant - geopolitically - location.

On top of that, Turkey and Russia have internal problems, and could possibly get an internal patriotism boost from a foreign war - particularly if it has low casualties for them and the outcome they desire.

One of the realpolitik factors that is significant here is economic. Simplifying a bit by ignoring the 10% that isn’t oil or gas, Turkey buys 14% of Azerbaijan’s exports (oil and gas), and European nations buy 33% - they would prefer that continued, but Europe won’t accept the political flak of a war - especially one with human rights abuses. It has other sources of oil - as do possibly Israel and Georgia, and definitely Russia.

Of course, I understand Azerbaijan’s oil pipeline goes through Armenia, but attacking that would lead to a major escalation, and Armenia borders its enemy’s backer, not Russia.

Geopolitically, apart from the competition between Russia and Turkey, authoritarian Iran is also close enough to get involved, and also has a history of intervention in others nations. However, I wonder if Iran can spare the resources for another foreign entanglement, especially given the effect of the pandemic inside that nation? I doubt Iran would get involved unless an event occurred such as a massacre or large scale abuse of Azerbaijanis (e.g., inside Armenia or Nagorno-Karabakh).

I don’t know anything about the quality of military forces of these nations (which have all largely inherited Soviet weaponry), nor what is happening with regard to military movement, but on paper, Azerbaijan would seem to be strongest. It is perhaps significant - and prudent - that Armenia has gone to the European Court of Human Rights for help.

One of the reports from this week is that Turkish backed fighters in Syria have gone to Azerbaijan, and are dying “in their dozens”. They’re tough, battle-hardened fighters, but Nagorno-Karabakh has, after all, lasted for several decades.

Another source of potential foreign fighters for Azerbaijan could possibly be various violent extremist groups that have been, based on a media report I recently read (and included in one of my recent news posts), rebuilding their strengths after apparently being wiped out. Azerbaijan apparently has the second highest proportion of Shia in the world, after Iran: would that make them inclined to accept such help if it turned up?

The crucial factor there would probably be Turkey’s attitude, and I suspect they would be disapproving of such measures. Again, if a massacre of similar problem occurred, it may be difficult to stop such involvement occurring.

The onus seems to be on Armenia to make sure Nagorno-Karabakh “fights fair”, and that depends on how effective third parties will be. If a massacre occurs of Armenians, it will be hard to hold back Russia, which shares a border with Azerbaijan, and, from the war it had with Georgia in 2008, knows something of fighting in the region.

However, Russia isn’t rushing to help its possibly injudicious ally.

Unfortunately, I don’t consider the European Court of Human Rights will have a significant direct influence on Azerbaijan, Turkey or Russia.

Cutting off military aid isn’t likely to happen, despite US Democrats urging an end to US military aid, as I suspect the bulk of the aid is from backers - and Israel is supplying at least Azerbaijan with cluster bombs.

The main external pressure that is likely to lead to an outcome is sanctioning Azerbaijan’s oil sales.

That may have to be combined with someone telling Armenia not to shoot their mouth off so much (see my disparaging remarks about macho attitudes above).

Ultimately, Nagorno-Karabakh may have to accept something like being an autonomous region within Azerbaijan (third parties are probably too concerned about their own internal tensions to support a clear signal favouring the right to self-determination over sovereignty), but Azerbaijan will also have to accept the need to stop discrimination.

Overall, provided no-one does anything majorly foolish, I consider there is a good chance of ending this war without it expanding - which is still too late for those already killed or harmed.

I don’t have good hopes, however, that Nagorno-Karabakh’s situation will be resolved in the near or even medium future.

Having worked through all that, I now want to put down some brief dot points on risk management.

This is what I actually wanted to cover, when I first conceived of the article, but it’s grown a fair bit so I will just list a few dot points.

Now, there are risks on all levels - from the individual to the world - involved in this situation. I’ll ignore the military aspects in the immediate front line conflict, but that still leaves us with:

Risks for individual civilians to manage:

- before the conflict, it may have been possible accumulate

food, water disinfection tablets, and the like, as survivalists do, but, in this

instance, that’s hard to do when living hand-to-mouth - and, even if one could,

it can be difficult when there is a long time interval between problems (which

is a lesson the entire world is relearning about pandemics) as the stored

food, etc has a limited life.

Accumulating empty sand bags and shovels is more likely to be useful.

However, as a general principle everywhere in the world, it is good to have two weeks of essential supplies available; - a better risk management option would be to relocate (which also applies to those in the shadow of volcanoes, or at risk of landslides, floods, and - of particular relevance to Australia - bushfires), but apart from the difficulty of finding the money to do so (and a nation to call home, and a job once you have arrived there), that can be devastating because of ties to that region (part of my heritage is Irish, so I have some feeling for this);

- once the conflict arrives, risk management will be about the safest way to find clean water, food, shelter, and medical aid, which may involve things like hiding during the day and moving at night, living in basements or caves, and never relaxing - movement can only occur after checking for planes, snipers, etc. Syria has shown the world what this is like, but it has occurred elsewhere - for instance, during the siege of Vicksburg during the US Civil War;

- for individuals living in democracies, educate others of the risks and the need to manage tensions;

Risks for towns to manage:

- the major issue for towns to manage is the provision of services - i.e., manage the risk of loss of essential services. This has been a part of sieges, and probably Sarajevo is the example that most people in the West can relate to;

- otherwise, it is similar to the disaster preparation that many municipalities do all over the world - the main difference is that actions may have to be extended beyond the typical two weeks of disaster planning (after that, towns and cities switch to recovery mode, ideally, but that won’t be possible for some time to come in a conflict situation). Places of refuge, routes for evacuation, etc are all a requirement;

Risks for businesses to manage:

- the best risk management is not to go into conflict zones - and yet businesses do that, time after time. We saw it during the “rebuilding” of Iraq, for instance (one wastewater treatment plant I worked on [from Australia] was in Afghanistan, and I recommended changing it from a highly mechanised activated sludge process to a simpler lagoon process for a range of reasons [easier to operate, more stable for the wide mix of inflows, etc], but also because it is harder to blow up a hole in the ground). If you do go into a conflict zone, you need to:get advice from experts on security - including for local employees;

- prepare plans for evacuation and other

contingencies. One company I worked at (in Australia) had procedures for

riots, several have had procedures for violent extremist attacks, and I know at

least one has performed a health emergency evacuation.

Make sure the plans can be triggered by those in distress (even if, for instance, by a missed phone call), and make sure they CAN and WILL be activated from a place of safety; - if warranted, provide appropriate training (e.g.,

knowing from the sound whether a gun has been fired towards or away from you),

which is training provided by the Rory Peck

Trust, Syria’s

White

Helmets,

and several

aid

and other organisations.

Make sure this includes residents of that nation; - make sure you have adequate cash and other resources for whatever may happen, including insurance of your employees (irrespective of the legal situation, morally you owe then that). Your people, not your short term profits, are your greatest asset;

- DO

NOT IGNORE OR UNDERESTIMATE SIGNS OF UNREST.

It can be human to do so when things seem to be going well - to you, but I have always remembered a media article a few months before the Bougainville Civil War which showed a few scrappy looking rifles in the boot of a car. The journalist was dubious about whether anything would happen, but it did - to the tune of tens of thousands dead over a ten year period, and the closure of what “was once the world's largest open pit copper gold mine generating over 40% of PNG's GDP”. The journalist looked at things, and missed what matters most: people.

This is a point for all businesses in the USA to consider, especially given the open display and use of weapons by white supremacists and the one-sidedness of many of the security personnel in recent months;

- Building on that last point, for businesses that are already in a conflict or at risk zone:

- relocation, with employees, is the most

preferable option with regard to safety ad certainty, but also the one that is

least likely to be practicable.

As an interim step, it is worth diversifying into other locations, even if that requires diversifying your main line of business - that can help with normal economic fluctuations as well; - address as many other of the points listed above as is possible - in particular, plan, and prepare (including practice) for putting that plan into action. The training that schools in the USA give for active shooter situations is an example of what could be considered for adults (outside the USA, normally only required for those going into conflict zones), although there are concerns about their use for children;

Risks for governments to manage:

- The first priority for a government is to hold together under incredible stresses and strains. This will be a time that hindsight should be left in the hind reaches of minds and mouths;

- Next ensure adequate logistical provisions for

those doing any fighting for you. If you can’t, you will lose - it’s that

simple, even if it will take time. Governments will have experts to advise on

the military matters (possibly including a switch to guerrilla warfare),

but the means of production are - or should be - a government expertise.

Again, preparation is key - plan, consider the lessons of history, re-plan, consider the feedback from trial runs, re-plan, and repeat; - Main point: make sure no-one - including in the

forces doing the fighting - does anything stupid. I think it was Von

Clausewitz who wrote about the risk of one brash or over-confident officer

putting entire strategies at risk - that can happen as a result of, if you are

not careful, your own propaganda, so don’t do too much on that front! This

should be within the capabilities of governments, as it is similar to

preventing hate crimes during times of peace.

In the current situation, one fighter doing something egregious could give the enemy an excuse to escalate.

On that, remember that in the current Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, the least well governed player has nuclear weapons . . . ;

Risks for regions to manage:

- firstly, work to avoid an escalation - note the preceding dot point;

- next, seek to contain or manage the harm. Seek to minimise the disruption to other nations, ensure refugees are managed in accordance with international requirements (the UN can help with that);

- third, seek to minimise the current conflict. This is where things like sanctions have their role, and will rely on regional organisations - the CIS might be good one for the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, for instance; and

- finally, seek a long term, permanent solution. While the conflict or tensions exist, your entire region is at risk.

Find a solution.

This may require finding and working with a trusted or respected

organisation / nation / individual(s) (such as, in Africa, “The

Elders”, in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh, the European Court of Human

Rights [ECHR]

has become involved at Armenia’s request), regional bodies (such as the African Union

or, in the case of Nagorno-Karabakh, the CIS),

or nations that are big enough and adequately dispassionate enough to get

people talking seriously.

Russia is possibly large enough to do so, but has been historically aligned

with Armenia so the issue of dispassion could be up for debate. However, in

this current instance, they haven’t moved to help Armenia, so maybe

they could play a peacemaking role . . .

Failing Russia, possibly Pakistan would be considered acceptable as a mediator

- Europe would likely be rejected by one side or the other.

One thing is certain: if the Armenian residents of Nagorno-Karabakh are driven

out, the war will continue for decades - just ask

the Kurds

about that.

My final comment is a reminder that all the above is still occurring in the ongoing genocide against the Rohingya in a region too insignificant geopolitically to get major commitments from the world (although some action has been taken), but a tragedy that is still as morally serious as anything else.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.